© Alexa Palmerini

A history of the garden

The history of West Side Community Garden is a rich one. This parcel of land was once part of a diverse coastal oak-pine forest populated by the Lenape people of Manhatta. The surrounding landscape included hills, valleys, forest, wetlands, beaches, ponds and streams, and over 1,000 species of plants and animals. Understanding the ecological history of this place inspires a deep appreciation for our existing urban wildlife and unique green spaces.

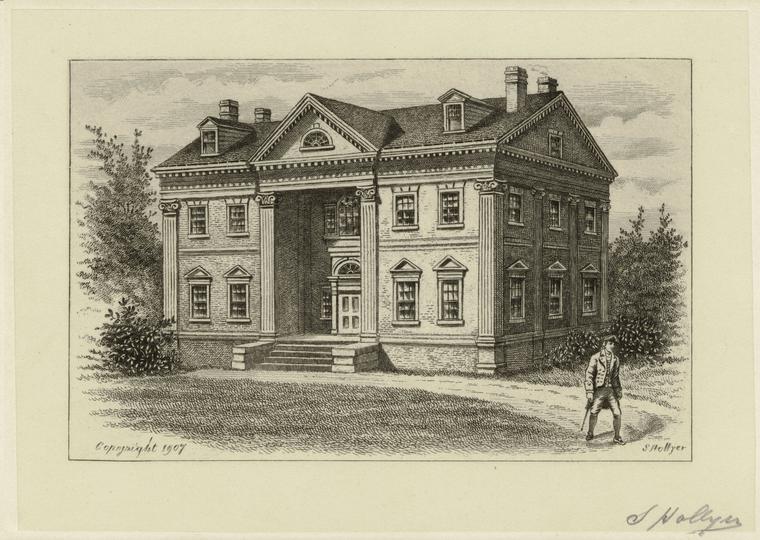

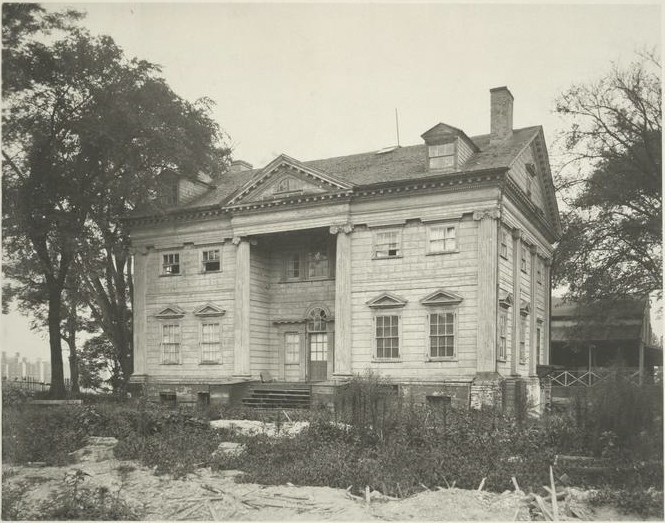

In the early years of the European settlement of New York City, the Dutch had named the area ‘Bloemendall’ (valley of flowers), but when the English gained an upper hand, they renamed the region ‘Bloomingdale’. Later, in 1760, the present-day site of the garden was part of 300 acres – including meadows and an orchard – acquired by Englishman Charles Ward Apthorp. A Boston lawyer and financial agent, Apthorp built a grand Palladian mansion on the highest hill at what is now the intersection of Columbus Avenue and 91st Street. The garden property, land now occupied by WSCG, was probably the mansion’s back or front yard.

As the American Revolution heated up, Apthorp abandoned his mansion and escaped on British Governor Tryon’s ship. The mansion, later named Elmwood, served as George Washington’s headquarters during the British northerly advance in the late 1770s. As the war progressed, Elmwood became the headquarters for consecutive British generals Howe, Clinton, Cornwallis, and Carlton.

After the war, Apthorp was indicted for treason but was never tried. He returned to his mansion and lived there with his wife and ten children until 1797, when his wife died of yellow fever. Elmwood, the mansion, and the 300-acre land were soon put up for sale. It was described in a New York newspaper advertisement as follows:

Three hundred acres of choice rich land, mainly meadow, with two fine orchards, an exceeding good house elegantly furnished with views of the East and North rivers. Two–story brick house for overseer and servants, a wash house, cyder house and mill, corn crib, pigeon house, large barn, hovels for cattle, large stables and coach house. Handsome pleasure garden in the English taste, kitchen garden well furnished with fruit trees, a good landing and wharf on the river.

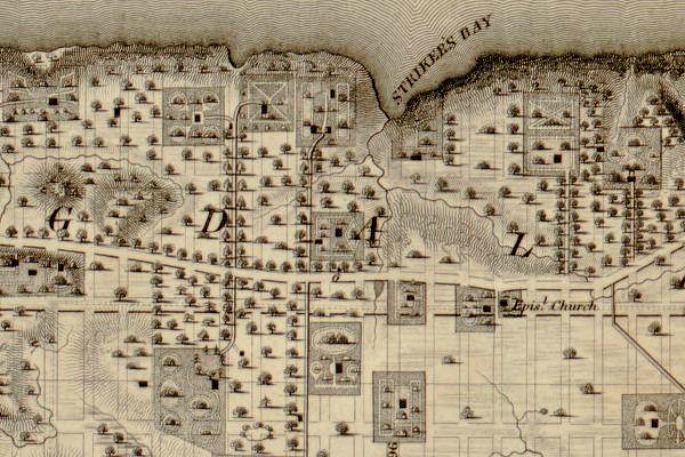

A map of the wealthy suburb once known as Strycker’s Bay, which stretched from 86th to 96th Streets and incorporated the land on which West Side Community Garden now sits.

Sold to William Jauncey and then to Colonel Herman Jauncey Throne in 1828, the Elmwood mansion fell into disrepair, becoming a beer and dance hall known as Elm Park. It was the scene of the Orange Riot of 1878, when Catholic Irish clashed with Protestant Irish marchers on their way up Western Boulevard (now Broadway) to celebrate the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne.

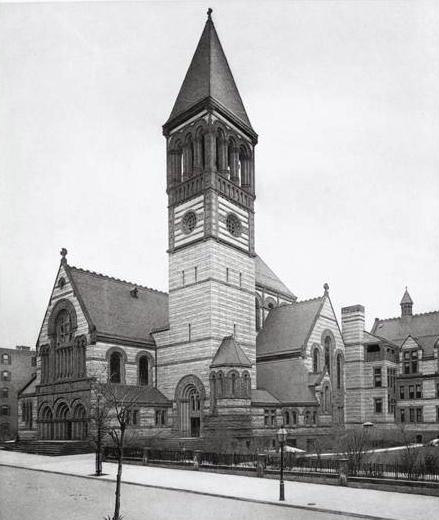

In 1888, when the Board of Streets ordered the opening of 91st Street and the surrounding area, the Elmwood mansion was torn down and replaced by the Episcopal St. Agnes Chapel. The meadows and fine orchards of 18th-century Bloemendall were replaced by rows of apartment houses on Columbus and Amsterdam Avenues and by brownstones on the side streets between the avenues. Other fine dwellings were built on Central Park West and on Riverside Drive.

Amid the surrounding developments, a one-and-a-quarter acre portion of the original Bloemendall was degraded over the succeeding years. During the 1970s, the neighborhood began to be developed as part of the West Side Urban Renewal Area (a project that commenced in 1962 and ran from 86th to 97th Streets, between Amsterdam Avenue and Central Park West). The lot gradually went from SROs (single room occupancy hotels) and affordable housing to rubble, and it soon became known as ‘strip city’, attracting all sorts of nefarious activities, including the dumping of stolen cars that were stripped down for parts. Children walked through the debris as a short cut to PS 166, and it was generally an eyesore. It was eventually named ‘Renewal Site 35’ by the City of New York.

© Trust for Public Land

© Trust for Public Land

Neighbors and parents got fed up and banded together to find a solution, and in 1976 they gained access to the land from the City, cleaned it up, and started to grow vegetables and flowers there. The garden space blossomed, but land tenure was uncertain.

In 1985 developer Jerry Kretchmer and architect Joe Wasserman’s proposed site development plans for the garden and contiguous space were approved by the city over a plan put forth by garden members. After Kretchmer and Wasserman purchased the plot, members moved into action to preserve their garden. With the help of the Trust for Public Land, the gardeners formally obtained and incorporated into the West Side Community Garden a 501(c)(3) tax exemption, and an engaged board of founding members – Tom Thies, Charles Jones, Judith Rohn, Jannie Burkette, Dee Parisi, and Carol Klein – looked for solutions to protect the property. Board president Tom Thies reached out to the City and negotiations began.

Under the terms of the agreement that followed, the developer paid for the design and for half the cost of the construction of a 16,000 square-foot garden (about a third of the garden’s size at its full build-out). WSCG was to raise the other half, or $170,000 of that total, which included the construction of the garden infrastructure, and the underground water and electricity necessary to maintain it for the long term. WSCG was also to remain open every day and ensure that all events on the site were free of charge. In return, the developer would receive the right to build taller buildings on a site nearby on Columbus Avenue.

It was a stretch to raise that kind of money, but WSGC members made it happen. The Trust for Public Land helped close the deal with a $20,000 bridge loan. In 1988 WSCG learned it was not going to receive a long-term lease, but instead would get the deed in perpetuity as long as the space was kept functioning as a non-profit and the garden kept open to all. It was a huge win. As it turned out, Jerry Kretchmer became involved as a supporter of the garden, and contributed funds for the hiring of the landscape architect, Terry Schnadelbach, who designed the multi-purpose garden space. Awarded the Philip N Winslow prize in 1991 for communal restoration and best landscape design of a public space, the garden now includes a floral amphitheater and public seating areas, flower beds and vegetable plots.

“We essentially filled a void,” reflects Tom Thies on the saga of West Side Community Garden and the example it has set for the unquantifiable value of community open space in New York City. “We started out offering a temporary solution to the problem of an eyesore of a mostly demolished site that had been a place for illegal activity and garbage dumping. We ended up turning it into something for which the people in the neighborhood feel a real sense of ownership.”

FURTHER READING

Articles

Books

Jane Garmey, City Green: Public Gardens of New York, 2018 [NYPL]

WEST SIDE COMMUNITY GARDEN

123 West 89th Street (between Amsterdam Avenue and Columbus Avenue)

Manhattan, New York City

McCann Art & Design © 2019 West Side Community Garden